Theme [theem] (Noun)

-

a unifying or dominant idea, motif, etc., as in a work of art.

Mechanics [muh–kan-iks] (Noun)

-

the technical aspect or working part; mechanism; structure.

I chose these definitions carefully, to delineate the difference between the overarching aesthetic experience versus the underlying game engine that makes gameplay possible. Normally, theme and mechanics work together to provide a complete gameplay experience, especially where licensed properties, like Firefly or Doctor Who, are concerned. But this is not strictly the case in every instance.

There are, for example, games in which the accurate depiction of the theme is the main source of interest for the player, and the mechanics are really only there as a means to reinforce the theme rather than provide ludic interest. The purest form of this (Theme 4, if you will) would be a game of ‘pretend’ like the childhood games of Cops & Robbers or Doctor’s & Daleks, where there are no mechanical underpinnings to the games at all, and play proceeds based upon whatever the group agrees will reinforce the illusion of being a masked bandit, or genocidal cyborg with a plunger and egg whisk for arms.

On the other hand, there are games in which the interesting interplay of game mechanics, and the skill at handling those mechanics determines the ‘fun’ level of the game. In some cases, the mechanics define the gameplay experience so thoroughly that any theme laid over them is only so much window dressing. The pure form of this (again, off the end of our scale at Mechanics 4), would be building a car. Unless the mechanics function in perfect alignment, car no go! And the joy of driving is entirely predicated on the mechanical quality of the car and the driver interaction with it.

Let’s look at a few examples, one that exemplifies Theme over Mechanics, one at the opposite end of that scale, and one that represents a good balance between the two.

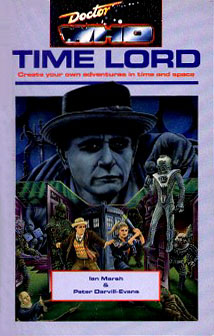

THEME 3: THE TIME LORD RPG (1991)

Back in the very early nineties, two years after the original series had bowed out, Ian Marsh and Virgin Publishing released a Doctor Who role-playing game: Time Lord – Create Your Own Adventures in Time and Space.

Back in the very early nineties, two years after the original series had bowed out, Ian Marsh and Virgin Publishing released a Doctor Who role-playing game: Time Lord – Create Your Own Adventures in Time and Space.

This was the second such attempt at an RPG based upon the series, and it couldn’t have been more different from its predecessor in design. Whereas the first RPG was simply a restatement of the generic set of RPG rules used in FASA’s previous game, Star Trek, with a Doctor Who make-over, Time Lord was built from the ground up to mechanically reflect the realities of the Doctor Who television series.

Almost every rule reinforced the theme, with little care as to how things worked outside of television reality. Genre Tropes of the series were given mechanical life, like the Screaming special ability, which allowed a companion to cry out for help (and be heard) across any distance, through miles of tunnels and labyrinths, or even across the gulfs of space (someone luckily left a communicator open, or something), so that the Doctor could come to their aid. It could even be used as a weapon, in some cases (as it was in the episode Fury from the Deep). Silly? Possibly, but very in character for the television series.

Another good example existed within the combat system. As long as a character is moving or behind cover, it is exceedingly hard to hit them with gunfire. Even when they are one area away! Again, silly? Not if you take into account the fact that, due to the restrictive size of the studio spaces the production team had to work with, almost all the firefights on the show took place within scant yards of each other, but few people got hit (unless a group of enemies concentrated their fire on a single target, like an extra or tragic supporting character, which is also covered in the rules).

Add extensive rules for scientific research (including an in-game time segment known as the Research Turn), cutting through doors and walls (a common way to create tension in the series), and creating MacGuffins (pseudoscientific devices or solutions that resolve the story), and you can see that Time Lord is an excellent example of a game that can easily be rated Theme 3.

THM♎MEC: FIREFLY – THE BOARDGAME

Like a lot of folks, Firefly really pressed all the right aesthetic buttons for me, and I was a might irritated when it was cancelled due to corporate shenanigans at Fox. So when Gale Force 9 released a licensed board game, I was right in line to get a copy.

Like a lot of folks, Firefly really pressed all the right aesthetic buttons for me, and I was a might irritated when it was cancelled due to corporate shenanigans at Fox. So when Gale Force 9 released a licensed board game, I was right in line to get a copy.

The issue with licensed properties, from my perspective, is trying to strike that balance between theme and mechanics. I want the game to reflect the goings on in that particular fictional universe, but at the same time, I don’t want Candyland with Browncoats and images from the show instead of gingerbread men and candy themed aesthetics (“Damn! I’m stuck in the Reaver Swamps of Miranda again!”)

The Firefly Board Game, however, manages to hit both sides of the equation pretty equally. The objectives and overall aesthetics do a great job of capturing the theme of the series (“Get a ship, get a crew, keep flying”), but also presents a variety of interesting mechanical twists that keep the game interesting and challenging from a ludic perspective.

One of the key ways I think you can judge the balance of a game like this is to consider how well the mechanics function with a stylistically similar theme. For example, the Firefly mechanics could also, with very few tweaks, be suitable for a game of 18th century piracy on the high seas, or maybe even a mob family type game. They are too linked to the thematic essence of small time transport/smuggling missions and operations to be useful for, say, a global conquest or economics game (not without a great deal of modification, at any rate), but within that limited thematic scheme, you could reskin the game fairly easily.

MECHANICS 3: MONOPOLY

Monopoly is the board game boogeyman for many folks, and for certain ludologists, it is the perfect example of how not to design a game. I tend to find this opinion over-exaggerated, especially since very few people have ever actually played the game according to its actual rules, relying instead on the oral tradition passed down for generations: the erroneous Free Parking rule alone can be said to account for much of its reputation as an extremely long and frustrating game. And yet, even with that reputation, it is still one of the best selling and most well known board games in the world, having spawned hundreds, if not thousands of variations.

Monopoly is the board game boogeyman for many folks, and for certain ludologists, it is the perfect example of how not to design a game. I tend to find this opinion over-exaggerated, especially since very few people have ever actually played the game according to its actual rules, relying instead on the oral tradition passed down for generations: the erroneous Free Parking rule alone can be said to account for much of its reputation as an extremely long and frustrating game. And yet, even with that reputation, it is still one of the best selling and most well known board games in the world, having spawned hundreds, if not thousands of variations.

But, just how different, mechanically speaking, are those variations?

For the most part, that answer is: not at all. No matter what version of Monopoly you are playing, whether it’s Star Wars Monopoly, Harry Potter-opoly, or Dallas Cowboys-opoly, you still roll two dice, move your pawn in a clockwise direction around a board separated into exactly the same number of squares, buy, rent or sell property, or draw cards. It doesn’t matter whether the game’s currency is in dollars, Galleons, or Imperial Galactic Credits, you still get 200 of them when you pass “Go,” and the most expensive property on the board, whether it be Hogwarts, the Death Star, or Dallas Cowboy Stadium (which, funnily enough, many of us here in Texas also call the Death Star), is still to the right of that space.

So as you can see, the theme of the game is pretty much inconsequential to the gameplay, itself. There might be minor mechanical variations to an individual version of the game (like Doctor Who’s 60 minute speed play variation), but it is extremely rare for those to make enough of a difference to change the basic play of the game, which is recognizably Monopoly, and is of little mechanical use for anything else. Aesthetically speaking, you don’t ‘feel’ like a wizard/jedi/Dallas Cowboy when playing, and nothing about the buying and selling of property to try and bankrupt your opponents fits particularly well with any of the above, thematically speaking. This makes Monopoly an iconic example of Mechanics 3.

COMING NEXT…

If you have any comments or suggestions on the material covered here, feel free to sound off in the comments section. I’m always open to new points of view on what is, after all, a very complex subject. I’ve already had one commentator on Facebook provide me with some insight that actually changed my perspective on the subject of the next post: Simplicity vs. Complexity, which is actually a much more complex and deep subject than you might imagine…