Interaction [in-ter-ak-shuh n] (Noun)

-

reciprocal action, effect, or influence

Isolation [ahy-suh–ley-shuh n] (Noun)

-

the state of being isolated (6. a person, thing, or group that is set apart or isolated…)

Read this if you want a first hand account of the Diplomacy experience…

Though fifth in this series, this is, perhaps, the most important question when it comes to game aesthetics: how much do the players interact with each other during the game and how does that interaction affect game-play? After all, gaming is largely a social activity and it is rare to find solo games that are as satisfying to play as the equivalent N-Player game.

It should be noted that not all games with heavy player interaction are necessarily competitive in nature, and there is a subset of ‘cooperative’ games: games where all the players team up against the game itself. These, by their nature, require a high degree of player interaction as cooperation is paramount to the success of the group as a whole. Arkham Horror, The Lord of the Rings and Shadows Over Camelot (although that particular game includes a traitor mechanic that introduces a small amount of competitive play back in), are all examples of cooperative games.

As with the previously discussed aesthetics, the two ends of the scale represent entirely different styles of play which might be good or bad depending on the tastes of the player, or even the circumstances of the moment. I enjoy games designed around pure player interaction (like Diplomacy, a clear example of an Interaction 3 game), but the constant scheming and intense negotiations, although immensely satisfying, can be tiring. In addition, games with a high player interaction factor allow other players to team up and/or freeze you out due to fear of your gamesmanship, which can make the game a lot less fun to play. As such, my desire to play games at this level of Interaction tends to depend entirely on how much time and energy I have, and who I’m playing with.

Solo games, of course, are excellent for those times when you have no one else to play a game with, and were much more popular in the early days of the hobby, before the internet made instant gaming with others, anywhere, at any time of the day, possible. The downside of the solo game is the procedural generation methods they use to keep the endgame unpredictable because, as we discussed earlier, random chance and human mutability are two very different types of unpredictable.

Solo games, of course, are excellent for those times when you have no one else to play a game with, and were much more popular in the early days of the hobby, before the internet made instant gaming with others, anywhere, at any time of the day, possible. The downside of the solo game is the procedural generation methods they use to keep the endgame unpredictable because, as we discussed earlier, random chance and human mutability are two very different types of unpredictable.

Of course, computer games are very good at simulating human intelligence, but this requires thousands of lines of code, programmed by a master of the game, to create a decision tree of such complexity that it would be unwieldy to use for a tabletop game. So you’ll find that the most pleasing solo gaming experiences are typically digital, or analog with a digital interface (like X-Com).

Most games fall somewhere along the middle of that scale, with some player interaction, as well as some personal player activity that is isolated from outside interference. In Tiny Epic Galaxies, for example, player activity and the current game state may drive some of your decisions, but what you do with your dice, whether to reroll them and what order to play them in, and how you spend your resources, is entirely up to you, and is cannot be hampered by others.

An important element to consider when judging how strongly a game leans towards the Interaction end of the scale is whether the game allows a player to win without involving other players. The same applies to solo games, but from the opposite perspective: how much power do opponents have to block a player’s path to victory?

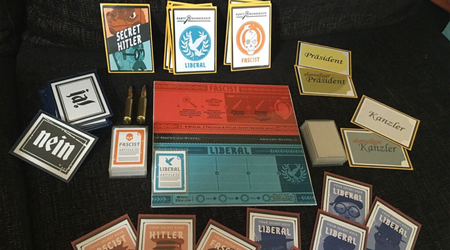

INTERACTION 3 – SECRET HITLER

Again, we are only going to give examples of the far ends of the scale and the middle, starting with a game at the far end of the Interaction scale: Secret Hitler. This is a game in the style of Werewolf, where one player is secretly the future fuhrer, and the rest are either fascists trying to put Herr Hitler in control, or liberal lawmakers trying to either identify the future dictator and eliminate him, or get a more sane government installed before he can come to power.

There are couple of random elements in the game: the distribution of identity cards appointing players as liberals, fascists and Hitler, before the game; and the random distribution of fascist vs. liberal laws, which serve to sow confusion as to who is a fascist and who is a liberal, during the game. The rest of the game is about trying to figure out who is who, by making accusations, arguments to support those accusations and, eventually, putting bullets in people’s brainpan, all of which is purely based on player interaction.

Now, there is the option to say nothing during the game, and just vote ‘Nien!’ on every proposal put forward, fascist or liberal, but eventually, you will have to pass a law, sometimes not a law you would have liked to pass. Those laws will influence people’s perceptions of you, and these perceptions can be colored by your silence and get you shot as easily as anything you might have said. As the song goes ‘If you choose not to decide You still have made a choice,’ so it’s best to pick a side and get into the fray.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” ― Edmund Burke.

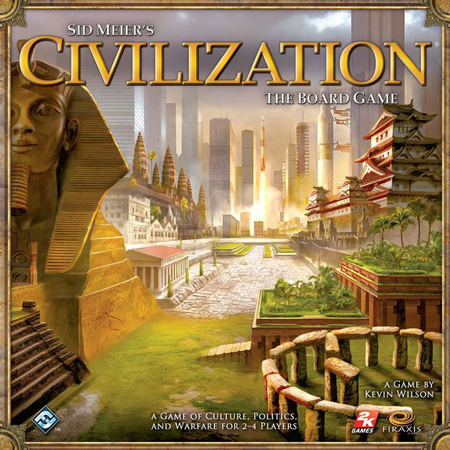

INT♎ISO – CIVILIZATION (2010)

As mentioned above, and as odd as it sounds, gauging the Interaction level of a game usually boils down to how easy it is to isolate oneself from interaction and still prevail. In games like Diplomacy or Viktory II, there is no possible way to play (much less win) without interacting with at least one other player (Interaction 3). In games like Illuminati, almost every play affects another player, and players can team up on a single opponent and keep them weak the entire game, making victory almost impossible (Interaction 2). These are all high Interaction games.

As mentioned above, and as odd as it sounds, gauging the Interaction level of a game usually boils down to how easy it is to isolate oneself from interaction and still prevail. In games like Diplomacy or Viktory II, there is no possible way to play (much less win) without interacting with at least one other player (Interaction 3). In games like Illuminati, almost every play affects another player, and players can team up on a single opponent and keep them weak the entire game, making victory almost impossible (Interaction 2). These are all high Interaction games.

Civilization (like most Euro-style games), is more balanced. A player can spend the whole game developing culture, technology and/or gold, and never actually interact with the other players directly. But everything they do tends to affect the other players indirectly, typically through the denial of certain unique resources. A player can choose to trade, war or otherwise ignore their opponents as they see fit, and many times, a group of players who love the building aspect more than the competition aspect, will leave each other alone for the whole game, only trading when they need a specific resource.

The ability to pursue victory by a variety of paths helps to minimize conflict, as does the slow acquisition of resources, and high cost of war. But the option to interact is still available, and can strengthen both parties, in the case of trade, or weaken one (or both) in the case of war. It also makes it extremely hard to ‘team up’ against one player effectively until the late game, which rarely benefits all parties concerned, so even if a player chooses (or is forced) to go it alone, they are in with a chance.

As such, Civilization gameplay has a balance between Interaction and Isolation.

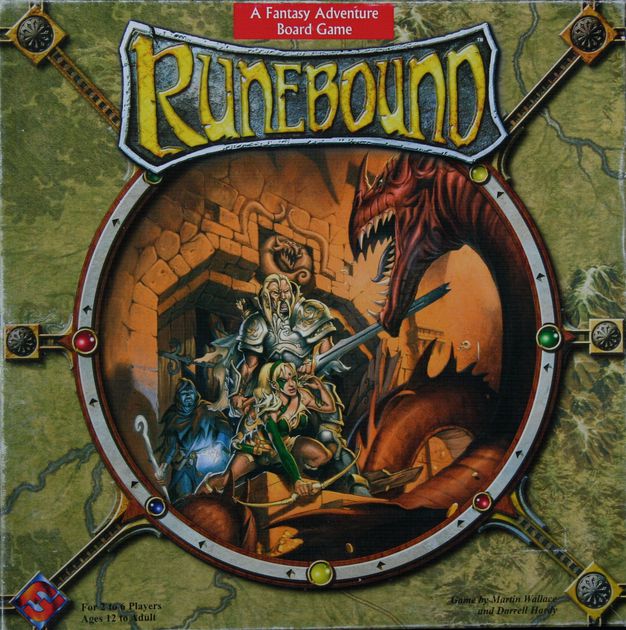

ISOLATION 3 – RUNEBOUND (2004)

Not all Isolation 3 games are single player. Runebound is pretty much a solo game that happens to tangentially involve other people. You go about your turn, encountering spaces and gaining in power, but nothing the other players do can affect your path to glory, outside of scoring important items and experience faster so that they can defeat the big bad first (a process that is painfully random). You live or die by your dice and a few simple decisions.

Not all Isolation 3 games are single player. Runebound is pretty much a solo game that happens to tangentially involve other people. You go about your turn, encountering spaces and gaining in power, but nothing the other players do can affect your path to glory, outside of scoring important items and experience faster so that they can defeat the big bad first (a process that is painfully random). You live or die by your dice and a few simple decisions.

The other players don’t even get to roll the dice for the monsters you fight, as they would in Talisman (the game that Runebound seems to take its cues from), as they have none: the monsters are completely static and combats are determined by your dice rolls alone. Other players basically sit around and wait for their turn to come along and the only true interaction comes when someone wins and everyone helps clear the game away.

COMING NEXT…

How much of the endgame is determined by your skill, or the power of your pieces? We’ll consider that question in the next installment…

Pingback: GAME AESTHETICS: INTRODUCTION… |