Agency [ey-juhn-see] (Noun)

9: the state of being in action or of exerting power; operation:

Linearity [lin-ee-ar-i-tee] (Noun)

1: the property, quality, or state of being linear (relating to the characteristics of a work of art in which forms and rhythms are defined chiefly in terms of line.)

As I mentioned in the introduction to this series, the only truly defining feature of games that seems to hold up to serious academic scrutiny is that they are interactive, in the sense that you can play them. Not all games are equal in the interactivity department, however, and there is great variation in the range of activity allowed to a player from game to game.

This is not, altogether, a bad thing. By restricting options, a game will often increase focus on those elements that most strongly define it, and improve the gameplay experience. The Firefly boardgame, for example, doesn’t need a detailed combat system, Star Fleet Battles style shp sheets, or role-playing mechanics to handle personal encounters. Too much detail in these areas would just bog down play, lead to other players being bored, and really detract from the main focus of the game: Find a crew. Find a job. Keep flying. The simple systems in place, instead, focus the game towards that goal, while giving the players a taste of what it is like be the Captain of a ship in the Verse.

Problems arise when a game takes this too far, not by necessarily restricting options, but by restricting the effect player decisions have on the actual endgame. Some games take this so far that any player interactivity is reduced to meaningless activity while one awaits an end to the game that they have had absolutely no control over.

Note that this lack of control does not automatically imply indeterminacy, as anyone who has playeda Choose Your Own Adventure book can attest to. Sometimes the lack of data to make informed decisions can lead to seemingly random ends. False choices, where one option is clearly better than the other, can lead the player right where the author-designer (an intentional distinction) wants them to go, regardless of how the player feels about the matter.

So in the case of Game Aesthetics, we would define games with a range of options that allow the player to affect the endgame, as having Agency. Games which restrict that ability to affect the endgame would be described as possessing Linearity.

THE ENDGAME

The definition of Endgame, in this case, is a bit fluid, in that it can encompass a variety of in-game, player-centric goals. In Twilight Imperium, a great deal of fun can be had in creating a sprawling trade empire, and providing options for the player to do that, rather than engage in physical or political conflict, is a form of Agency, even if the player eventually loses (although making it a sub-standard, or ‘False,’ choice reduces the value of that Agency). The player was able to shape their actions to realize their ideal endgame.

And in some cases, the endgame is not the only measure of agency. Role-playing games, for example, don’t really have an endgame, in the traditional sense, as the characters persist and carry on from game to game, but the ability to go anywhere and do anything, within the limits set by the game environment, should rightly be seen as providing the players with a great deal of agency.

SO CANDYLAND SUCKS?

The difference between Agency and Linearity should not be construed as a commentary on whether a game is good or bad. In some cases, a game’s design goals go beyond gameplay, especially when a game is created for art (Journey), political commentary (September 12th), or serves a developmental purpose (Candyland). Sometimes it’s not the destination, but the experience, that is important.

And sometimes, folks just want to have a bit of fun without being swamped with Decisions & Data points (which sounds like a really boring RPG about systems analysis). This is why games like Phase 10 are so popular, and why most gamers have at least one quick play, Beer & Pretzels style game sitting in their closet. Sometimes you want to think. Sometimes you want to drink. And that, my friends, is how Beer Pong was born…

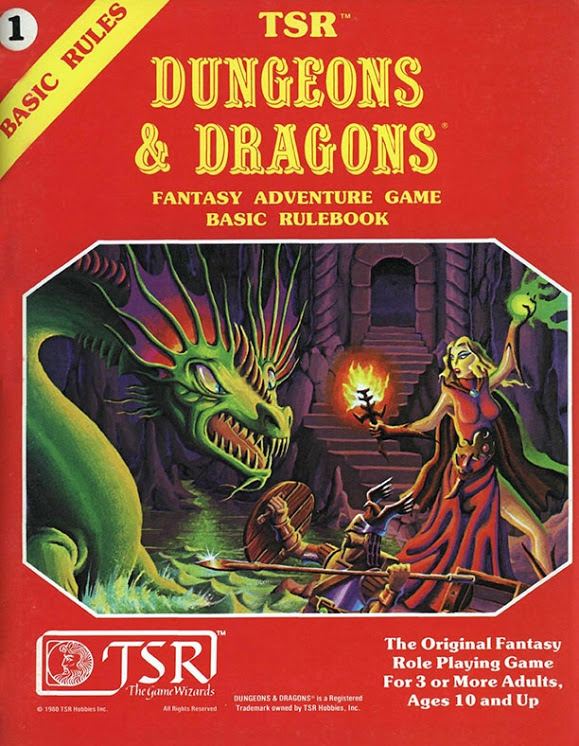

AGENCY 3: DUNGEONS & DRAGONS (1974)

When it comes to Agency, you’ll find that role-playing games heavily populate that end of the scale, because their very nature as ‘Theatre of the Mind’ allows the players vast scope to do whatever they can imagine. When confronted with a cave, the payer can enter it, check it for traps, try to find a way around it, have lunch in front of it, whatever they can think of, so long as it doesn’t conflict with the judgement of the referee (“No, you can’t climb the rock-face of the cave, it is too steep and smooth…”).

This extends into the exploration of the world, which, theoretically, has limitless horizons. The referee can throw out adventure hooks left and right, but if the players are curious about a mountain that popped up in the west during their last foray into the wilderness, then they might go there, instead. Combine this sandboxing playstyle with the concept that the characters’ actions have lasting effects on their world, and change it in ways that are persistent and meaningful, and you have the perfect recipe for almost total player agency.

Dungeons & Dragons was, of course, the first published game to fully embrace this play-style, and the original has a DIY nature that ensured that not even the written rules were sacrosanct, and many campaigns were run using house-rules or entirely new rules sets that would eventually evolve into published competitors (Tunnels & Trolls, Runequest). As the first such game, and the one with the loosest structure (so loose that Gygax created AD&D to serve as a Rosetta Stone for tournaments and official play), it stands as the paragon of Agency 3.

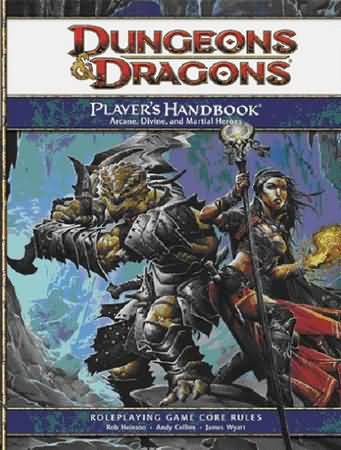

AGN♎LIN: DUNGEONS & DRAGONS (2008)

I would argue that an RPG cannot be Linear (and I’m sure many would disagree with me). There are games on the market, Descent for example, that adopt RPG tropes and aesthetics, but they lack the extensive Agency of a true RPG and are clearly miniature board-games.

The 4th edition of Dungeons & Dragons is a game that skirts the edge of linearity, however. It’s notthat the players have any less agency than they did with its predecessor; the spirit of role-playing ensures that players with the right attitude and a willing DM can sandbox just as much as their grognard forefathers. But they can also do that with Descent, or any other game for that matter. Role-players gonna role-play, no matter what the rulebook say. That’s how RPGs were born in the first place.

What puts it at the edge of the RPG envelope are the mechanics (remember, we are looking at the game itself, not necessarily the use it is put to). They were heavily focused around two activities: character builds and combat. Both of these (in a bizarre inbreeding of influences) resemble MMOs in many ways, even borrowing terminology from games like World of Warcraft. And great detail was put into making sure those activities were as interesting as possible, with tons of options and mechanical wrinkles, and many more added through expansions as the product life cycle ran its course. The net result was that the rules encouraged these activities above all others, while social interaction and other activities were given short shrift (a common complaint in the early days of 4E).

Due to the mechanical complexities of all the possible power permutations, synergies, creature abilities and environmental rules, character builds, and especially combat, each took a lot of time (sometimes whole sessions) to complete. As such, there was less spontaneity and a tendency for 4E DMs, especially those new to RPGs, to build more linear stories and fill them with set piece battles with limited branching. And because the skill and feat system heavily defined what the characters could and couldn’t do, there was a tendency for players to do less thinking outside the box, stifling their own agency in the process.

In an odd sort of way, with its miniature combat focus and wargaming-like codification of what specific actions the players could attempt, 4th Edition fit the original title of D&D, Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Pencil, Paper and Miniature Figures, much better than the original edition did.

LINEARITY 3: CANDYLAND

I give a lot of grief to Candyland, but not without good reason. It is, for me, the worst example of game design. It is totally Linear, in that there is not a single decision that you make in the game that affects the end result. In fact, I could just shorten that previous sentence to ‘there is not a single decision you make, period,’ and I would still be accurate.

I give a lot of grief to Candyland, but not without good reason. It is, for me, the worst example of game design. It is totally Linear, in that there is not a single decision that you make in the game that affects the end result. In fact, I could just shorten that previous sentence to ‘there is not a single decision you make, period,’ and I would still be accurate.

From the start you draw a card (or spin a spinner in the latest versions, which makes the game even more random). The card tells you where to go. You move your piece there. Continue until someone reaches the end. All the joy of Snakes & Ladders, but with the added fun of being stuck in a molasses swamp for interminable periods of time. The only choice you make is whether to play the game or not (I always choose the latter, and by my reckoning, that means I win without even opening the box).

My personal animus aside, Candyland still sells because, as we discussed above, it has design goals beyond gameplay. In this case, Candyland is a developmental tool for children. It teaches them a few important things:

- Color recognition.

- How to follow rules.

- How to play with others in a friendly fashion, win or lose, i.e. sportsmanship.

Hmm, I’m getting the strong odour of linearity, with a healthy wiff of Indeterminacy. Did some wino pass this before you put it in my glass…?

I would also argue that it teaches real lessons about how life can be arbitrary and unfair, and that you just need to suck it up and keep on truckin’, but I’m probably projecting. Let’s face it, in the case of this game, I’m like a jaded wine snob trying to choke down a bottle of Three Buck Chuck. My tastes have grown well beyond such simple fare, but the tiny rednecks in my house love it, and they are who it was designed for.

Whatever the case, Candyland is clearly an exemplar of the Linearity 3 game.

COMING NEXT…

How much does the game encourage player interaction? We’ll talk about that next…

Pingback: GAME AESTHETICS: INTRODUCTION… |