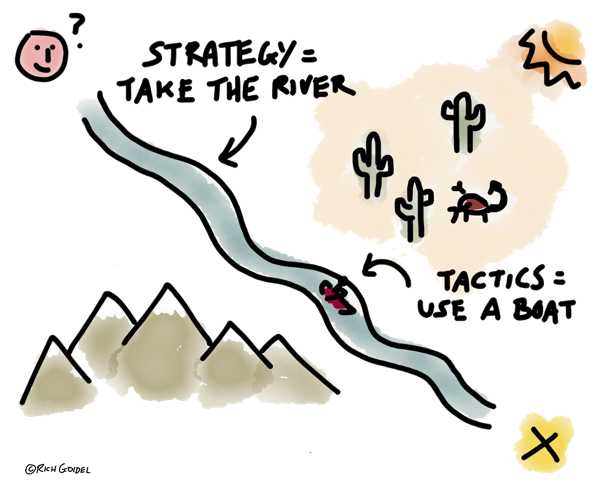

Tactical [tak-ti-kuh l] (Adjective)

-

of or relating to a maneuver or plan of action designed as an expedient toward gaining a desired end or temporary advantage.

Strategic [struh–tee-jik] (Adjective)

-

pertaining to, characterized by, or of the nature of strategy (1. a plan, method, or series of maneuvers or stratagems for obtaining a specific goal or result)

Originally, I only had six aesthetic dyads. One of the issues I consistently had, however (as touched upon in my post on Simplicity vs. Complexity), was this: if simplicity and complexity do not speak to a game’s depth, what does? How do you define ‘depth’ as an aesthetic?

Originally, I only had six aesthetic dyads. One of the issues I consistently had, however (as touched upon in my post on Simplicity vs. Complexity), was this: if simplicity and complexity do not speak to a game’s depth, what does? How do you define ‘depth’ as an aesthetic?

The need for a seventh dyad to address this was further inspired by a response from Jose Zagal, a fellow academic, to a post I made in the Role-play Theory Study Group on Facebook. In his response, he shared a paper with me on Gameplay Aesthetics that approached the subject from a lexical examination of common terminology, or as he put it, “by broadly examining how people who play games describe gameplay.”

While our scope, goals and approaches to the subject differ considerably, I did find some similarities between Jose’s work and mine, as well as a few new concepts that provided essential elements for further consideration. In particular, the adjective clusters that defined Cognitive Accessibility and Scope, seemed to speak directly to the concepts I was attempting to define. Further discussions with a local friend of mine, Dr. Adam Brackin, helped me to further refine the concept and, after some noodling, I came up with a set of terms that seem to clearly, and neutrally define my new dyad.

BASIC CONCEPT

The essential definitions I chose reflect the difference between short-term reaction and long-term planning, which directly affect the perception of ‘depth’ in a game.

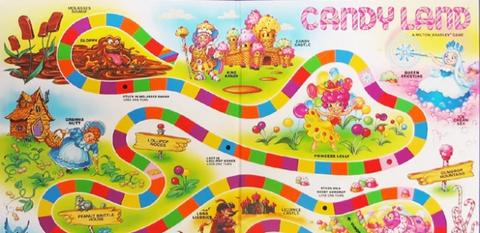

In some games, the ability to react to situations on the fly is much more important than making a long term plan. In games at the far end of the Tactical Focus scale, long term plans are essentially meaningless, as the flip of a card, the roll of a die, or the perfidy of an opponent (or ally) can change the game space so thoroughly that you must rethink everything on a regular basis.

In some games, the ability to react to situations on the fly is much more important than making a long term plan. In games at the far end of the Tactical Focus scale, long term plans are essentially meaningless, as the flip of a card, the roll of a die, or the perfidy of an opponent (or ally) can change the game space so thoroughly that you must rethink everything on a regular basis.

Games like this typically are random enough, or the moves powerful enough, to prevent much mitigation through pre-planning (outside of, say, holding a few key cards in your hand until the right moment), and the winner is typically the player who can grasp the immediate situation, and take best advantage of it on a moment to moment basis.

In games that weigh more heavily towards the Strategic Focus end of the scale, the ability to plan ahead, and create contingencies that can mitigate short term losses, is the largest factor in victory. In these types of games, a player can have temporary setbacks, even large ones, but few actions are so powerful as to upset the equilibrium of the game in a single move. It takes a series of moves to really upset a player’s overall strategy, if they have one, of course. If they don’t, they are pretty much doomed to lose, as reactionary play typically allows the opponent to control the flow of the game.

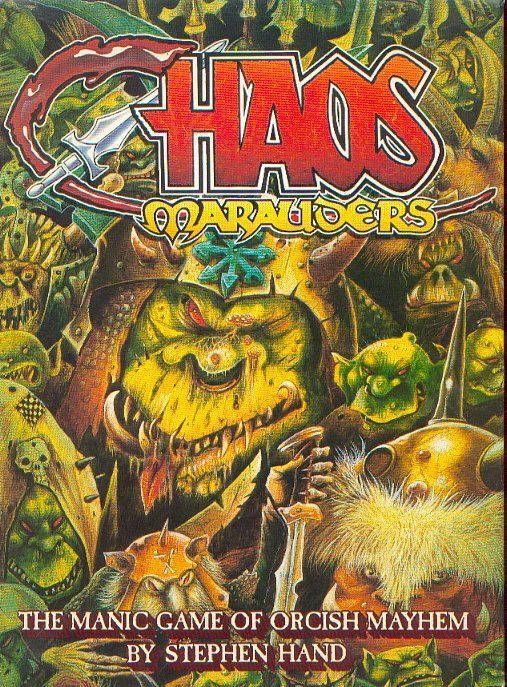

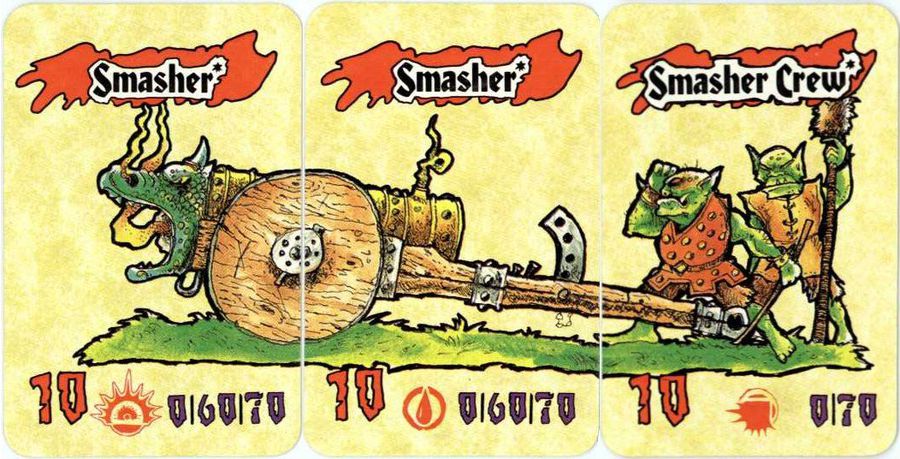

TACTICAL FOCUS 3: CHAOS MARAUDERS

I collected just about every game Games Workshop put out in the 1980’s, and a good deal of the one’s from the early 90’s as well. They ranged quite a bit in quality of design (and Chaos Marauders was a straight up reskin of an existing German game) but one thing they all had in common was a propensity towards really cool themes, weird art, and fun mechanics.

I collected just about every game Games Workshop put out in the 1980’s, and a good deal of the one’s from the early 90’s as well. They ranged quite a bit in quality of design (and Chaos Marauders was a straight up reskin of an existing German game) but one thing they all had in common was a propensity towards really cool themes, weird art, and fun mechanics.

Chaos Marauders was a tongue-in-cheek, Beer & Pretzels style card game that played as chaotically as the title suggested. Players took it in turns to draw cards, one at a time, and placing them into one of three battlelines until they drew a card that ended their turn, or they completed a battleline. When a battleline was complete, it could be used to attack weaker, incomplete lines, by rolling the hilariously monikered Cube of Destruction, a six-sided die with 5 Orcish Eyes and a single Symbol of Chaos. Roll an Eye, and you destroyed the enemy and took their stuff. Roll a Chaos Symbol, and your line broke, and the enemy took your stuff, instead.

First player to complete three battlelines ended the game and points were totted up to determine the final victor.

Although there are a few more mechanical wrinkles (cards with exception based rules, specific procedures for completing battlelines, scoring, etc.), the game is really about taking what you’re given and making the most of it without any real idea of what might turn up next. You do have decisions to make, like how long you want your battleline to be (between short, relatively weak, and quick to complete; or long, strong, and likely to be attacked before you can finish it), or when, where, or even if, you build a war machine, but almost all of them are made in the dark. You just sort of pray to Gork (or Mork) that the right cards come up.

Although there are a few more mechanical wrinkles (cards with exception based rules, specific procedures for completing battlelines, scoring, etc.), the game is really about taking what you’re given and making the most of it without any real idea of what might turn up next. You do have decisions to make, like how long you want your battleline to be (between short, relatively weak, and quick to complete; or long, strong, and likely to be attacked before you can finish it), or when, where, or even if, you build a war machine, but almost all of them are made in the dark. You just sort of pray to Gork (or Mork) that the right cards come up.

And turnarounds in the game can be very swingy. The best potential scoring line can be kept one card from completion by a steady succession of bad draws, only to be eliminated by an opponent who manages to pull that one card you couldn’t find, giving all your loot to him and forcing you to start (literally) back at square one. But equally, he might roll a Chaos Symbol on the Cube of Destruction and lose everything to you!

All that being said, as with most card based games, card-handling skills come into play as players become familiar with the deck contents, and veteran players can get a feel for the ‘flow’ of the game, making educated guesses about what might pop up based on frequency and what cards are already in play. But still, with 112 cards, play is largely reactionary, making Chaos Marauders a Tactics 3 game.

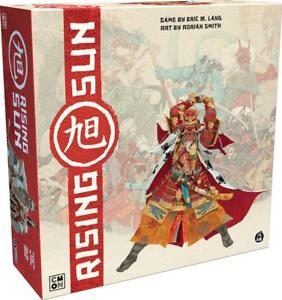

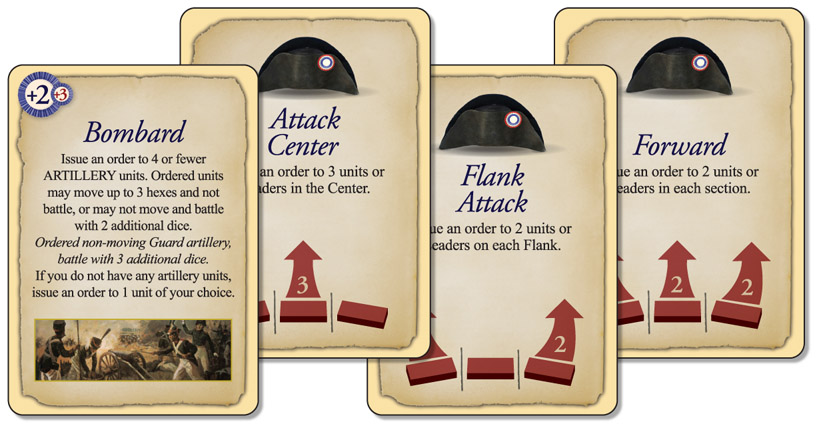

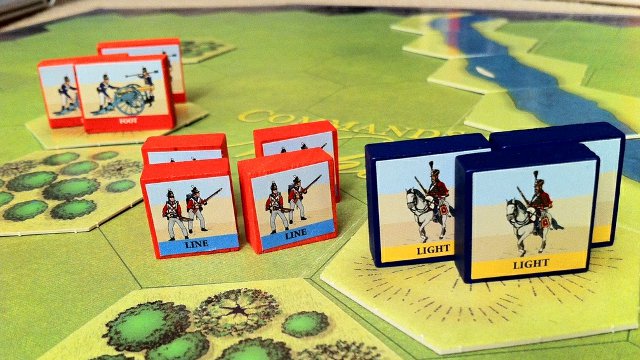

TF♎SF: COMMAND & COLORS NAPLEONICS

Wargames run the gamut of ratings, from Tactical to Strategic, typically based upon the scale of the conflict modeled by the mechanics. Something like Bolt Action, with a focus on a small squads of individual soldiers is inherently Tactical in nature, as the units engage in quick exchanges of individual gunfire and brutal hand-to-hand combat, using whatever temporary advantages they can gain from terrain, position and luck to eliminate the enemy. The status of individual soldiers, whether dead, injured, pinned, etc., is of great importance to the player.

Wargames run the gamut of ratings, from Tactical to Strategic, typically based upon the scale of the conflict modeled by the mechanics. Something like Bolt Action, with a focus on a small squads of individual soldiers is inherently Tactical in nature, as the units engage in quick exchanges of individual gunfire and brutal hand-to-hand combat, using whatever temporary advantages they can gain from terrain, position and luck to eliminate the enemy. The status of individual soldiers, whether dead, injured, pinned, etc., is of great importance to the player.

In grand-strategic games, like Axis & Allies, however, a single infantry piece attacking into an adjacent country would represent a hundred such games of Bolt Action, all resolved with the roll of a single six-sided die. And there are typically several infantry pieces involved in the average A&A battle. The actions and fate of the individual soldier means little in a battle where thousands of casualties occur with a single roll of the dice.

The Command & Color series, however, has a scale that fluctuates considerably, depending on which battle you are attempting to recreate, from company to division level. What makes it a good balance of Tactical vs. Strategic Focus, however, is the fact that it while it allows for forward planning (Strategic Focus), it also has enough indeterminacy and restrictions on potential action to make sure that those plans occasionally have to be adjusted on the fly (Tactical Focus).

The biggest hindrance to forward planning in the game is the random draw of order cards, which are used to command your troops (move them, fight them, etc.). Any solid strategy revolves around a successive series of pre-planned moves, and this requires playing the the right cards in the right order to command the right troops in the right section of the battlefield. This is actually a fairly accurate portrayal of command and control issues from the period, where trying to coordinate an army through a series of hand-written orders, carried by horseback to the individual commanders, had issues (such as the ‘miscommunication’ that led to the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade).

The ability for a player to hold a number of cards in their hand (the better their in-game general, the more cards they may hold), however, allows the player to plan ahead more effectively by ‘collecting’ cards until a plan can be put into action, while using other cards to feint and probe the enemy positions. The sectional nature of the battlefield along with the inherent restrictions in the order system also forces the player to consider the bigger picture at all times, and to occasionally sacrifice a flank or the center for a gain in another area, if the gains outweigh the losses. This actually encourages strategic play by rewarding the general who waits until the right moment, and the right place, for an all out push, and punishes reactionary players who make piecemeal offensives without the proper resources to follow through or reinforce their units.

The ability for a player to hold a number of cards in their hand (the better their in-game general, the more cards they may hold), however, allows the player to plan ahead more effectively by ‘collecting’ cards until a plan can be put into action, while using other cards to feint and probe the enemy positions. The sectional nature of the battlefield along with the inherent restrictions in the order system also forces the player to consider the bigger picture at all times, and to occasionally sacrifice a flank or the center for a gain in another area, if the gains outweigh the losses. This actually encourages strategic play by rewarding the general who waits until the right moment, and the right place, for an all out push, and punishes reactionary players who make piecemeal offensives without the proper resources to follow through or reinforce their units.

On the other hand, the occasional need to counter an enemy push means that the player must also be able to properly read the situation and react accordingly, even if that means upsetting carefully laid plans. For example, it is often worth delaying a major offensive to pull back damaged units and allow them to regroup (or even to pull the enemy in for a counteroffensive). Combine this with the intricate nature of combat (including combined arms combat, forming squares, and the rock/paper/scissors relationship between units), and the game is as tactical as it is strategic.

Finally, the durability of units, mixed with the uncertainty of combat, add both tactical and strategic elements. The ability to survive attacks without loss of offensive capability, and counterattack, means that players are willing to make take more short term risks for long term goals (strategic focus). However, the ability to wipe a unit out with superior force, terrain usage and combined arms (tactical focus) means that sometimes, a player will be forced to react to the loss of important holding units immediately (tactical focus).

Finally, the durability of units, mixed with the uncertainty of combat, add both tactical and strategic elements. The ability to survive attacks without loss of offensive capability, and counterattack, means that players are willing to make take more short term risks for long term goals (strategic focus). However, the ability to wipe a unit out with superior force, terrain usage and combined arms (tactical focus) means that sometimes, a player will be forced to react to the loss of important holding units immediately (tactical focus).

So, overall, a balanced game.

STRATEGIC FOCUS 3: CHESS

It may seem strange that Chess hasn’t already popped up in one of these examples, but while it is a solid 3 in Mechanics, Simplicity, Determinacy, Player Interaction, and Player Skill, it is also the epitome of a game with a Strategic Focus.

Every game of chess can be divided into three distinct phases: the Opening, the first 10-15 moves of the game (and which, due to the beginning game state, has a wide variety of well understood strategies); the Middlegame, when there are still a good number of pieces on the board to threaten the Kings, who have typically castled; and the Endgame, the final phase of the game where the number of pieces has been whittled down considerably to two or three major pieces and some pawns.

Each phase has its own distinct set of strategies, made up of a multitude of small, tactical moves which serve to further the overall push towards a specific game state, but which individually, do not shift the equilibrium of play a great deal, at least not until the late middle, or early endgame. In fact, the individual worth of pieces is so subservient to the overall strategic picture, that it is common Chess practice to ‘sacrifice,’ or intentionally lose a piece, in order to further long term goals. Losing a battle to win a war, in other words, which is the ultimate expression of strategy over tactics (Strategy 3, in game aesthetics terminology).

UP NEXT…

So how do we determine if a game aesthetic leans one way or the other? And by how much? We’ll look at that in the next installment…

with the English language) two subtly different meanings.

with the English language) two subtly different meanings.