NOTE: I think I’ve got the Spambots under control, so, as a test, I’m opening comments for the first time in donkey’s ages. We’ll see how it goes…

At this point, our character has largely been subject to the whims and vagaries of the dice, their attributes and place in life largely out of their control. A single decision (their initial Trade) is made, but even that is heavily influenced by the circumstances of their birth.

At this point, our character has largely been subject to the whims and vagaries of the dice, their attributes and place in life largely out of their control. A single decision (their initial Trade) is made, but even that is heavily influenced by the circumstances of their birth.

At first, I questioned this decision, wondering if my basic premise (that of a literature professor replacing Gygax as the ‘father’ of RPGs) would result in a game with a more narrative, choice driven, character generation scheme and rules. After all, considering his profession, his approach would logically be more inclined towards a literature first, gaming second approach, whereas Gygax (and as a result, OD&D) was arguably more gaming first, literature second.

The fact remains, however, that the games of the time were largely simulationist in nature, so some semblance of that should show in the initial design. Considering the wargaming roots of the hobby, and our professor’s initial intent to create a game that gives life to the models in those very wargames, where success and failure, life and death, are so driven by the roll of the dice, it seems natural that his more narrative inclinations would be tempered by his simulationist background. Some sort of hybrid would emerge, where tools for dramatic situations outside of combat would be more thought out, but the role of random chance and tabular information would remain strong, and this is my best approximation of that result.

That said, we are now getting to the point of the process where the players will be making some direct decision for their characters…

4. TRADES

A Trade in the game allows the player to reroll Attribute dice when an action is taken to allow a character trained in a specific area to succeed more often (and suffer less Misfortune) while attempting certain tasks. In certain cases the Judge may decide that a specific Trade is required to even attempt the roll in the first place (as would often be the case with many tasks that require advanced education, like Engineering or Doctoring).

A Trade in the game allows the player to reroll Attribute dice when an action is taken to allow a character trained in a specific area to succeed more often (and suffer less Misfortune) while attempting certain tasks. In certain cases the Judge may decide that a specific Trade is required to even attempt the roll in the first place (as would often be the case with many tasks that require advanced education, like Engineering or Doctoring).

The term Trade is just a tiny bit incongruous here, because no one in the upper classes and aristocracy would ever demean themselves by referring to what they do as a ‘trade.’ After all, trades are what the hoi polloi engage in, not people of breeding and rank! But at the same time, the definition for trade is ‘a skilled job, typically one requiring manual skills and special training,’ which holds true for even a Duke, who must learn to read, write, manage large land holdings, and whip servants with force enough to dissuade impertinence (How dare you call Statesmanship a trade!) but still leave them capable of doing their work.

So, unless I think of something better, Trades it is.

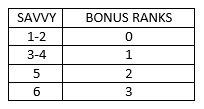

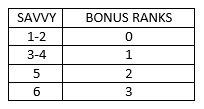

Our birth class will have given us a single Trade, and In this portion of character generation we will determine if our character has any additional Trade ranks due to being clever. This is determined by our Savvy Attribute:

These ranks can be added to our existing Trade, or used to learn a new one, from the list below. Each Trade has a brief description of the sort of things you might do with it, any starting bonuses you receive for taking that Trade at character generation, and basic starting possessions (if any).

NOTE: I removed Bureaucrat, Farmer and Servant from the list, as the last two (being just another form of laborer) are redundant and the first is fairly useless (from both an objective and subjective point of view). I’ve corrected the previous post in this series to reflect that.

Academic: A Trade that covers a wide variety of subjects of a book-learning nature, from sciences like Astronomy or Engineering, to liberal arts like History and Poetry, and everything in between. Can be used to recall knowledge, do research or impress others who find such things impressive (i.e. other academics).

Academic: A Trade that covers a wide variety of subjects of a book-learning nature, from sciences like Astronomy or Engineering, to liberal arts like History and Poetry, and everything in between. Can be used to recall knowledge, do research or impress others who find such things impressive (i.e. other academics).

At character generation, Academics gain 1 Expertise in this Trade without having to reduce their Rank. They start with D6 Books on various subjects.

Example Expertise: History, Engineering, Poetry

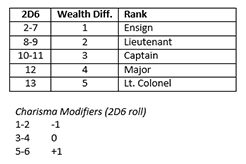

Aristocrat: This ‘Trade’ covers all the knowledge necessary to maneuver through high society, including knowledge of societal ranks, manners, and activities (like hunting, dancing, riding, etc.).

At character generation, an Aristocrat may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Charisma by 1. They start off with Very Fine Clothing, a Fancy Sword, a Thoroughbred Horse and a Servant.

Example Expertise: Dandy, Rake, Intrigue

Banker: Bankers understand everything about money and running financial institutions. This makes them naturally good at math, bookkeeping, financial negotiation and generally increasing wealth.

At character generation, a Banker may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Wealth by 1. They start off with Fine Clothing, a Money Belt, and a Riding Horse.

Example Expertise: High Finance, Accounting, Bureaucracy

Clergy: Members of the Church (the player should signify their denomination). They can use their sermons to inspire, intimidate. They know a great deal about religion (theirs and others) and many have basic knowledge in medicine.

Clergy: Members of the Church (the player should signify their denomination). They can use their sermons to inspire, intimidate. They know a great deal about religion (theirs and others) and many have basic knowledge in medicine.

At character generation, Clergy may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Luck by 1, representing the will of the Almighty to use them (for good or ill). They start off with a Holy Book and the ability to read, write and speak in 1 language for every Rank they have (one of which must be their native tongue).

Example Expertise: Vicar, Monk, Inquisitor

Craftsman: An artisan who makes a specific product, like shoes, barrels, etc. or provides a more general service like blacksmithing or silversmithing (the Judge will determine if your class level fits the work you do).

At character generation, Craftsmen gain 1 Expertise in this Trade (which represents their actual skill) without having to reduce their Rank. Whenever they work outside of this expertise, however, they suffer Disadvantage. They start off with Workman’s Tools specific to their Expertise. If they have Wealth of 3 or more, they also have a place of business and all the necessaries to run it.

Example Expertise: Blacksmith, Wainright, Mason

Doctor: This Trade represents a university trained physician, trained (if not necessarily competent) in all the most modern medical techniques of the day.

Doctor: This Trade represents a university trained physician, trained (if not necessarily competent) in all the most modern medical techniques of the day.

At character generation, the Doctor may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Saavy by 1. They start with a Doctor’s Bag, and Riding Horse.

Example Expertise: Battlefield Surgery, Psychiatry, Coroner

Entertainer: This Trade encompasses any all the entertainment arts, from drama, to music to demonstrations of mental or physical acumen. May be used for performing, creating new content and capturing an audience’s attention.

At character generation, Entertainers gain 1 Expertise in this Trade without having to reduce their Rank. They start with an Entertainer’s Kit that fits their Expertise.

Example Expertise: Acrobat, Actor, Violinist

Healer: This is the lower class version of the Doctor trade, uneducated in modern medicine but wise in the way of folk remedies (“Aye, paraffin and brown paper’ll fix that up right as rain…”) , herb lore, midwifery and the like. They often worked on animals as well, and were well versed in local folklore and gossip.

At character generation, the Healer may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Luck by 1. They start with a Healer’s Bag and a Knife.

Example Expertise: Plant Lore, Midwifery, Animal Care

Hunter: This is the Trade of game-keepers and poachers alike, and covers the tracking, stalking, shooting/trapping and cleaning of game, as well as living rough.

At character generation, the Hunter may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Dexterity or Vigor by 1. They start with a Musket, Ammo Pouch, Knife and D6 Small Animal Traps.

Example Expertise: Sharpshooter, Trapper, Tracker

Laborer: This Trade covers any sort of manual labor, from shovelling dung to serving the aristocracy (which impertinent types might imply is essentially the same thing). Farm laborers, drovers, sweeps, servants, etc., all fall into this category, which covers the ability to get the most done with the least effort as well as the ability to skive off and still get paid. Laborers with Expertise might be actual tradesman with some particular skill for making barrels, laying brick, etc.

Laborer: This Trade covers any sort of manual labor, from shovelling dung to serving the aristocracy (which impertinent types might imply is essentially the same thing). Farm laborers, drovers, sweeps, servants, etc., all fall into this category, which covers the ability to get the most done with the least effort as well as the ability to skive off and still get paid. Laborers with Expertise might be actual tradesman with some particular skill for making barrels, laying brick, etc.

At character generation, the Laborer may raise their Strength, Vigor or Mettle by 1. They start off with some sort of basic tool for their work, like a Hammer, Shovel, Servant’s Uniform, etc. If they have an Expertise and at least Rank 3 in Laborer, they are a Tradesman and may have Workman’s Tools for that particular trade.

Example Expertise: Bricklayer, Butler/Maid, Rat-catcher

Landlord: The management of properties, ensuring their maintenance and milking the most profit out of them, is the purview of the Landlord. They might be over a single building, large estate or even an entire Dukedom, but whatever the level, they must manage workers, pursue rents and occasionally act as the local magistrate for internal legal affairs.

A Landlord starts out with a holding to manage based on their Rank and/or class. A Rank of 1 indicates a single building or tenement, while a 5 or more indicates an estate of considerable size. Whether or not they own or simply manage it for another depends on their class and the Judge may increase the size of the holding if the character’s Title entitles them to more.

Example Expertise: Innkeeper, Mill Operator, Work House Owner

Lawyer: The Law, and everything to do with it, from trials to contract negotiation, is the domain of this Trade. They are empowered by the government to operate in a court of law.

Lawyer: The Law, and everything to do with it, from trials to contract negotiation, is the domain of this Trade. They are empowered by the government to operate in a court of law.

At character generation, the Lawyer may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Savvy by 1. They start with a number of Lawbooks equal to D6 x their Lawyer Rank, Lawyer’s Robes and a Powdered Wig.

Example Expertise: Criminal, Contract, Military

Merchant: Buying, selling and arranging the transfer of goods, across the country or across the globe, is handled by the humble merchant, who must be highly organized, mathematically minded, able to quickly evaluate the value of any object, and an expert haggler.

At character generation, the Lower Class Merchant starts with 1 Wealth rating in Trade Goods, a Wagon to carry them in, and a Draught Horse to pull the wagon. Merchants in the Middle Class start with a Warehouse, their Merchant rating in Trade Goods and a full wagon train to carry them. Upper Class Merchant’s have Warehouses (complete with land transport and D6 Wealth in Trade Goods each) and Ships equal to their Merchant Rating.

Example Expertise: Clothier, Spices, Sutler

Rogue: Pickpockets, burglars, cutthroats, swindlers and all the other villainous scum that populate the lower class slums of every major city in Great Britain, as well as the horse thieves, vagabonds, gypsies and charlatans that haunt the countryside, as well.

At character generation, the Rogue gains 1 Expertise in this Trade without having to reduce their Rank, to represent their main criminal vocation. They start off with Rogue’s Tools for that Expertise.

Example Expertise: Fence, Forger, Highwayman

Sailor: Covers a knowledge of river, lake and sea, how to traverse them, whether in small boats or as a member of the crew of a larger trading vessel or ship of the line, and live off of them.

At character generation, the Sailor may reduce may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Thews or Vigor by 1. They start with a Club and a Bottle of Spirits. There is a 4 in 6 chance that they know how to swim.

Example Expertise: Gunner, Navigator, Shipwright

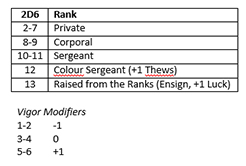

Soldier: Marching, fighting, shooting, living rough and working regulations to best advantage are all part of a soldier’s life. The enlisted ranks will also be well versed in digging trenches, building emplacements and other sorts of menial military labor.

Soldier: Marching, fighting, shooting, living rough and working regulations to best advantage are all part of a soldier’s life. The enlisted ranks will also be well versed in digging trenches, building emplacements and other sorts of menial military labor.

At character generation, the Soldier may raise their Thews, Vigor or Mettle by 1. Enlisted start with a Musket, Ammo Pouch, Backpack, Uniform and Hat – Shako. Officers start with a Fine Uniform and Hat – Bicorne.

Example Expertise: Artillery, Cavalry, Light Infantry

Spy: This Trade is not one gained through normal channels. It represents a character who specifically works for His Royal Majesty’s government to root out information on some particular form of enemy, foreign or domestic. From street level informants in the London underworld, to master spies in Spain, seeking advantage for their armies and countering the agents of the enemy, they are masters of stealthy infiltration, the acquisition of secrets and the knife in the back.

At character generation, the Spy may take another Trade at Rank 1 as a cover. This cover may be of any class equal to less than the Spy’s birth class. They start with whatever equipment their cover starts with, as well as a Poignard, Spyglass, and Falsified Documents.

Example Expertise: Disguise, Infiltration, Seduction

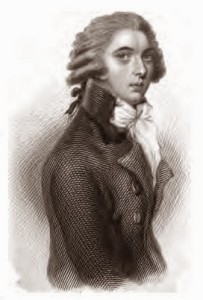

Statesman: Politicians, diplomats and attaches to the royal court, those with this Trade are master negotiators with some real world authority and/or power, which they wield as effortlessly in the halls of Parliament as they do the drawing rooms of high society, and everywhere in between.

Statesman: Politicians, diplomats and attaches to the royal court, those with this Trade are master negotiators with some real world authority and/or power, which they wield as effortlessly in the halls of Parliament as they do the drawing rooms of high society, and everywhere in between.

Statesmen who have a Peerage may sit in the House of Lords. Statesmen who can afford to sit in the House of Commons (Wealth 4 or better), or can find someone who will financially support their candidacy, may run for election to do so.

At character generation, the Statesman may reduce a single Attribute by 1 to raise their Charisma by 1.

Example Expertise: Diplomacy, Intimidation, Truth Detection

EXPERTISE

You may pick an Expertise for your Trade by reducing it one Rank (to a minimum of 1). You gain Advantage on any roll for which your Expertise applies. Each Trade will have a few examples of Expertise that might be chosen, but the Judge may allow others if they consider them narrow enough to be useful in a few specific circumstances.

LITERACY

LITERACY

Characters in the Upper and Middle Classes are assumed to have had at least some schooling and know how to read, write and do basic math.

Those in the Lower Class will be largely illiterate, however, unless they have a Trade that the Judge determines gives them the ability (like Merchant or Entertainer – Actor).

The chance of literacy for everyone else in the Lower Class is 1 in 6.

LANGUAGES

A character may roll 2D6 and add their Savvy Rank: they know a number of additional languages equal to the result – 12. They must justify each language they take to the Judge’s satisfaction and he may decide to limit them to a lesser number of languages or simply declare that they only speak their own.

FINIS

So now we know who your character is and what they do. From this point we can take the information we have and use it to derive some purely mechanical info for use in the game, which we will do in the next post…

And again, these ratings are all very subjective: subject to personal opinion, the possible permutations of complex gameplay mechanics, and so on, but that is actually a strength. A game like Rising Sun might be designed with only a few true randomized elements, but the complexity of the system interactions, and the chaos unleashed across the board by certain moves or events, can often make it seem highly indeterminate and hostile to long-term strategy, which might make it extremely unpopular with the Eurogame crowd (and elicit laughter when people try to relate it to Diplomacy). But, despite this skewing of perception by personal experience, there is an average opinion that can be extrapolated from all of this, which can serve as some sort of clue as to how a game ‘feels,’ and that information can be very useful.

And again, these ratings are all very subjective: subject to personal opinion, the possible permutations of complex gameplay mechanics, and so on, but that is actually a strength. A game like Rising Sun might be designed with only a few true randomized elements, but the complexity of the system interactions, and the chaos unleashed across the board by certain moves or events, can often make it seem highly indeterminate and hostile to long-term strategy, which might make it extremely unpopular with the Eurogame crowd (and elicit laughter when people try to relate it to Diplomacy). But, despite this skewing of perception by personal experience, there is an average opinion that can be extrapolated from all of this, which can serve as some sort of clue as to how a game ‘feels,’ and that information can be very useful.

WHICH VERSION TO USE?

WHICH VERSION TO USE?

40 minutes, 15 dead. At this point, the few remaining villagers decided to head back to town for reinforcements.

40 minutes, 15 dead. At this point, the few remaining villagers decided to head back to town for reinforcements.

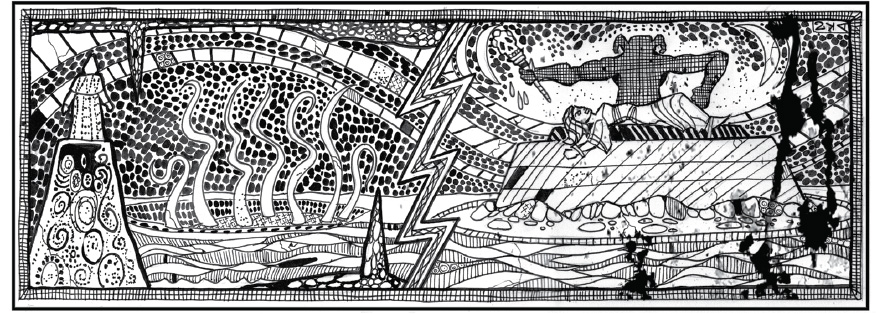

underneath the fort which contains a vast underground lake bordered by black sand. Trackers in the party identify the footprints of villagers being herded towards the sea by beastmen, while the elves study the ancient runic carvings on a giant menhir. Unbeknownst to the party, the words ensorcelled one of the elves, who surreptitiously led his brother up the stairs winding up the side of the giant stone. When they got to the top, they found an altar with a strange bowl shaped depression and the enspelled elf turned on his brother and attempted to offer him as sacrifice! His brother prevailed, however, and the poor possessed creature ended up with his own blood spilled upon the altar, and his body claimed by several gigantic tentacles that burst forth from the water to take him.

underneath the fort which contains a vast underground lake bordered by black sand. Trackers in the party identify the footprints of villagers being herded towards the sea by beastmen, while the elves study the ancient runic carvings on a giant menhir. Unbeknownst to the party, the words ensorcelled one of the elves, who surreptitiously led his brother up the stairs winding up the side of the giant stone. When they got to the top, they found an altar with a strange bowl shaped depression and the enspelled elf turned on his brother and attempted to offer him as sacrifice! His brother prevailed, however, and the poor possessed creature ended up with his own blood spilled upon the altar, and his body claimed by several gigantic tentacles that burst forth from the water to take him.

Clergy: Members of the Church (the player should signify their denomination). They can use their sermons to inspire, intimidate. They know a great deal about religion (theirs and others) and many have basic knowledge in medicine.

Clergy: Members of the Church (the player should signify their denomination). They can use their sermons to inspire, intimidate. They know a great deal about religion (theirs and others) and many have basic knowledge in medicine.

After some noodling on the cultural aspects of the character from the last post, I’ve settled on the following characteristics,,,

After some noodling on the cultural aspects of the character from the last post, I’ve settled on the following characteristics,,,

I think that this is one of those areas of design in which Luther, a literature professor, would differ from Gygax, whose game was essentially, at it’s heart, still very much a wargame in the traditional sense. OD&D characters were given attributes, a career class (which often served as their name as well) and some equipment, but rarely a backstory in those early days. They were characters in the sense that they were named individuals, but they still remained largely playing pieces (albeit, ones with much more agency) and the player was more like the Greek gods of old, guiding their mortal pawn and watching them live or dice by the throw of the cosmic dice, than actors playing a role.

I think that this is one of those areas of design in which Luther, a literature professor, would differ from Gygax, whose game was essentially, at it’s heart, still very much a wargame in the traditional sense. OD&D characters were given attributes, a career class (which often served as their name as well) and some equipment, but rarely a backstory in those early days. They were characters in the sense that they were named individuals, but they still remained largely playing pieces (albeit, ones with much more agency) and the player was more like the Greek gods of old, guiding their mortal pawn and watching them live or dice by the throw of the cosmic dice, than actors playing a role.